This week the NAHT published its report into the new assessment landscape following the abandonment of National Curriculum levels. Impressive, really, considering the fact that the DfE still hasn’t managed to provide its report on the consultation that closed four months ago!

The NAHT committee had much of sense to say, but I didn’t agree with all of it. I agree that it makes sense for schools to work in clusters to create and share assessment processes; I agree that we need a clear lead from the DfE & Ofsted on how we are to use whatever processes are put in place; I agree that assessment should be based on specified criteria, rather than simply ranking pupils; I also agree that it is unreasonable to expect schools to have everything in place for September, and so the interim use of levels is probably unavoidable, and perhaps even advisable for a short period.

It’s worth noting here that David Thomas (@dmthomas90) has written an excellent blog summarising his views on the report, and I agree with the vast majority of what he says about its strengths and weaknesses, although we disagree on the solution!

In particular, I welcomed the NAHT’s recommendation that whatever systems schools use, they should ensure that they

“assess pupils against assessment criteria, which are short, discrete, qualitative and concrete descriptions of what a pupil is expected to know and be able to do.”

The new National Curriculum – particularly at primary level – makes it clear what is expected to be taught in each phase, and in many cases in each year group for the core subjects. This helps to provide a starting point for identifying those assessment criteria. [Note 1]

However, where I part company from the NAHT report and others who have recommended similar processes is in the following recommendation:

“Each pupil is assessed as either ‘developing’, ‘meeting’ or ‘exceeding’ each relevant criterion contained in our expectations for that year.”

At first glance, this seems a reasonable suggestion, and is fairly based on the evidence that the NAHT received that there was little appetite for a simple binary system. However, what concerns me is that we will end up with a poor hybrid assessment vehicle. There are a couple of reasons for this.

Firstly, I suspect that the reason teachers were so reluctant to consider a “binary” is because of their long experience of sub-levels in the current system. Progress is hard to demonstrate across a whole national curriculum levels, and so the bastard sub-levels were introduced. However, if the NAHT proposal that criteria are “short, discrete, qualitative and concrete“, then this issue should not remain. Secondly, I suspect that by adding such vague statements as “developing”, we risk corrupting the most effective aspect of such a system.

Take, as an example, a simple objective that might be counted as short, discrete, qualitative and concrete. A school might include one criterion that a child can recall the 6x table. It seems that most of us could agree that this could be demonstrated by responding to random quick-fire questions as have been used for centuries. However, at what stage do we argue that a child is “developing” this skill? When they can count on in sixes mentally? When they can count up in sixes aloud? When they can recall at least half of the tables up to 12? And similarly, what constitutes exceeding that objective? Surely once you can do it, you move on to new objectives?

The only reason I can see for the developing/meeting/exceeding sub-grades is if we replace the current system of levels with a system of… well, levels. But even then, the criteria become too vague. After all, one objective then might be knowledge and recall of all tables to 12×12. But you could argue that as soon as a child counts in 2s, they are beginning to develop that knowledge. And when might we consider them exceeding it? When they learn the 13x table?

The major downfall of levels, in my opinion, was that their broadness became a failing when we moved to increasingly regular measures of progression. If we end up with statements that are so broad as to require splitting into thirds in the way proposed, then we might just as well simply update the levels.

So, what do I suggest as an alternative? Well, not for the first time, I’m going to suggest looking back to the National Numeracy Strategy of the late 1990s. The strategies were responsible for a lot of nonsense, but the NNS had a couple of real strengths, one of the greatest of which was its exemplification pages.

These pages not only provided examples for teachers to explore the ways in which statements could be interpreted (which is often the first challenge of interpreting a curriculum document), but more importantly they provided an overview of progression across year groups. It made it clear for teachers where their next steps were when children had met a particular outcome, and where steps could be put in place for those struggling.

If the NAHT is to go ahead with its proposal to work on a model document to create suitable assessment criteria, then hopefully it might begin too see that such an approach could be far more meaningful than the vague descriptors of development/meeting/exceeding.

A progression of key strands across the subject may run the risk of re-inventing the many attainment targets of of the late 1980s, but short measurable objectives could be organised in a manner to support progression and support teachers in identifying how best to support students who might be deemed to be ‘developing’ or ‘exceeding’ common objectives for the year groups.

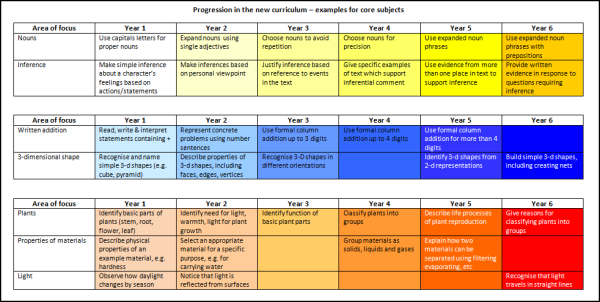

Some examples of objectives organised as possible outcomes in a progression for primary schools are shown:

It is very much a hastily knocked-up suggestion, far from a finished model. In an ideal world, groups of experts and specialists could work together to organise progression documents like the NNS example which could genuinely support teachers, and provide a framework of assessment exemplifications.

It would certainly be far more purposeful than simply using vague verbs to break up content.

[Note 1] Of course, much of this work might have been avoided if the DfE had followed the recommendation of the Expert Panel that it set up. Its recommendation is perfect:

Programmes of Study could then be presented in two parallel columns. A narrative, developmental description of the key concept to be learned (the Programme of Study) could be represented on the left hand side. The essential learning outcomes to be assessed at the end of the key stage (the Attainment Targets) could be represented on the right hand side. This would better support curriculum-focused assessment.

Michael, first of all thanks for pointing in the direction of the NAHT report, which was not on my radar.

When I read the suggested descriptors I had to smile. Our school uses the IPC and so we have adopted the IPC assessment descriptors, which are: beginning, developing and mastering. These relate to the skills objectives as described by the IPC documentation. Assessing “Knowledge” and “Understanding” objectives is left to schools/teachers to determine. One interesting facet of the IPC methodology is that the objectives are set out over a two year ‘mile post’, so KS2 is split into MP2 and MP3. (Each descriptor for each core skill objective is described in both teacher and student friendly language.)

So, for example, a student in Year 3/4 could be assessed in the same History objective over a two year cycle. In Year 3 he or she might pass through ‘beginning’ and be assessed at the end of Y3 as ‘developing’, but by the end of Y4 might be ‘mastering’. Another student may be quicker or slower to progress.

The comparison with the example you gave above in ‘progress in core subjects’ is interesting to me. Where I have some worries would be in the fixing of progression by Year Group. Once we go past the core subjects (English, Maths) I think it’s hard to make these incremental steps work in classroom practice. For example, would I really want to teach the science of plants every single year? The implicit consequence of the year-on-year progression model is that we are teaching all the core concepts in every year of school, as I wouldn’t wish to assess something I have not taught. It could just end up with curriculum overload again, unless as schools we take on the year-on-year model with a flexible approach.

I am watching the debate on replacing levels with great interest. I wish I could see a clear way forward but I believe any system developed is going to have to have a level of flexibility for professional judgement and implementation.

I should add that my school’s work with the IPC is somewhat undermined by the local (I work oversea) system of assessment, where KS2 students are expected to be graded in all subjects on a quarterly basis by the class teacher. Fall below 5 (on a scale of 0-10) by the end of the year and you could be asked to repeat the year. Let’s just say that we have a lot on plates trying to square that circle!

Thanks for your comments, Thom. I hadn’t appreciated the similarities to the IPC, which is interesting.

I agree that the progression is more challenging for foundation subjects in primary, but there are two strands to my post. Firstly, the indication of progression. As you rightly say, you would not necessarily teach about plants in every year of KS1 and KS2, but when teaching a unit, it would still be useful to know what comes next. So, in the example I’ve shown some aspects are not mentioned every year. I suspect that with a good deal more work on the model that more gaps would appear. However, it still clearly shows the next step if a child is “exceeding” the level expected of his/her age.

I agree that it would need some considerably greater thought – and it’s possible that a two-year cycle might be more effective in foundation subjects. I certainly think that the focus is – quite rightly – very much on the core subjects in primary.

Of course, the progression is necessarily separate from the assessment. As you have said, you might not teach a certain theme every year; that to me signifies the importance of ensuring that all children master the basic content required when it is delivered. The system of stating that children are “developing” their knowledge of, say, the parts of plants, is not good enough, if we are then going to leave that knowledge undeveloped until they have to try to catch up again two or three years later. It is for that reason that in assessment terms I prefer a shrunken list of key outcomes that we work to ensure that ALL children achieve.

It’s not an easy goal, but I think it’s a preferable aim to simply resigning ourselves to the presumption that some children will be forever developing, but never mastering the necessary knowledge.

Michael

Your reply makes me think about quite a few of the issues that we currently face in school when discussing assessment. With regards to knowledge I have a hard time thinking that the descriptors (NAHT or IPC) offer anything. Perhaps I am too concrete in my thinking but I feel you either know or don’t know knowledge. It is in the area of skills development that descriptors have something to offer, if written effectively.

Here’s an example of descriptors from the Science material in the IPC. The skill objective (for Y3/4) is ‘Be able to use simple scientific equipment’ (teacher version first, student version in brackets):

Beginning (I’m getting used to it):

The child uses simple scientific equipment with some help. Such use may not be sufficiently correct to produce accurate results. (I can use some equipment to carry out an investigation. My teacher helps me decide what to use and helps me use it.)

Developing (I’m getting better):

The child independently uses simple scientific equipment. Such use may not be sufficiently correct to produce accurate results. (I usually choose what equipment to use for our science investigations. My teacher gives me some ideas on how to use the equipment properly.)

Mastering (I’m really getting it):

The child independently uses simple scientific equipment sufficiently to produce accurate results. (I always choose my own equipment for science investigations. I use the equipment very carefully. My teacher says that all of my measurements are very accurate and that I see lots of detail.)

I should note that I don’t hold these up as exemplars of perfect practice, but they are a way that some teachers have tried to develop a more coherent assessment system. It is interesting to note that in the IPC documentation they also offer suggested ‘next steps’ that teachers can consider when feeding back to a student the current attainment (i.e. what you need to do to go from developing to mastering). I also know of one school that has done all the work you are talking about by taking the IPC descriptors for all year groups and put them in one single continuum of development, from PN to Y6.

Is this something closer to what you are describing?

In reality this is something very close to a rubric. I use rubrics a lot and have found them excellent tools for formative assessment, particularly with older students. However, they also have their limitations in that they will always be somewhat loose and moderation and professional discussion about what demonstrates each level of attainment needs to be discussion among colleagues. The other concern with rubrics is that they can easily limit student attainment at the top end, something that Alfie Kohn argues quite neatly. In practice I think the limitations are just something good teachers ensure are avoided.

As our school moves forward with assessment I think the key thing for us to remember is that we should endeavour to create an assessment model that makes sense to our students as much as it does to us. We need assessment tools that embed the ability to feedforward as much as feedback, which requires us to make sure assessment is completed with students, not done to them.

The descriptors you describe about using scientific equipment are exactly the sort of thing I worry about becoming commonplace. It seems reasonable, until you realise how much we are dependent on context, and how our judgement is so easily impaired.

For example, what equipment are we referring to here? Is it suggesting things like reading a thermometer to the nearest degree? A measuring cylinder to the nearest millilitre? Universal Indicator on a pH scale? Or choosing to use a sieve over filter paper? There’s too much room for disagreement, and so we end up with increasingly vague statements which do not serve to identify next steps clearly enough.

Personally, my view is that at primary level we’d be better ensuring that children had the necessary basic skills and knowledge that allows them to access the secondary curriculum with ease.

The statements you describe – not unlike those in the dreadful Science APP – offer too much room for key skills to be overlooked.Much better, I’d say, for us to agree that all children will reach Y6 knowing how to take accurate measurements using specific equipment. A binary measure, which is easy to teach, assess and target, and for which intervention is straightforward and purposeful.

As students move into secondary and beyond, rubrics may well be more suitable both for the breadth of skill and in the hands of subject specialists with a much tighter focus. However, at the moment we have too much time spent at secondary filling gaps that are concealed by vague statements of attainment.

Perhaps we ought to look again at what we consider “secondary ready” to mean? If I asked a secondary teacher what they really wanted all children to be able to do in their subject before starting Y7, I suspect we might have a fairly decent list of minimum expectations to work towards.

Michael

I understand your concern with vague statements and I often have felt the same way when entering a new year group of KS. Where I get concerned myself is when we ask for too much specificity in assessment. I have seen two consequences that give me cause for thought: firstly, when you create very specific measure of achievement you end up enabling the narrowing of teaching and learning, when assessment criteria determine learning, which I cannot help thinking is not exactly what Jay McTighe intended when he developed backward design. The second concern I have is in order to create specificity you multiply the number of objectives to be assessed. But that is only what I have seen in personal experience and so I am happy to be proved wrong in both cases.

Perhaps I am fortunate. I have taught in both Primary and Secondary and have also been a school leader in both. What I do know is that secondary teachers have very specific and concrete expectations for their incoming students and that if you asked each department for a list you would probably ed up with something akin to the earliest national curriculum, when we had assessment targets coming out of our ears.

What we have discussed here is really important stuff and while I might disagree with you on specifics I do agree that there is a big discussion that will have to be held in staffrooms across the country if we are gong to get anywhere worthwhile. It is gong to be interesting, if only because this is one of the few times I can remember the government handing over a pillar of education to those that teach.

Thanks again for your word, Thom – and I agree that actually what is important at the moment is that discussions like these happen, that we might thrash out the most effective systems.

I happen not to have an issue with the narrowing of the curriculum at primary level if it leads to ensuring that all students have accessed and learned an expected minimum, rather than the hit-and-miss outcomes we currently have.

I do agree that an excessive number of outcomes is highly undesirable, and I have written previously about the key objectives approach that was used in the old NNS, which I liked.

I suspect, actually, that in most cases secondary teachers would provide a fairly limited expectation of outcomes from primary school: the problems that so often arise in Y7 and beyond arise from the gaps in learning that is expected to be covered. For example, as a mathematician, I generally feel that if by Y6 all children were genuinely secure in written and mental calculations, could measure accurately and has a real number sense, including at decimal and fraction level, then everything else could be taught in the 5 years at secondary. What makes secondary teaching so laborious is constantly backfilling, in my view. It might be an interesting experiment to carry out…

Michael, as somebody who moved into teaching maths at KS3 for a few years I can tell you that I do agree regarding the key basics. However, I would argue that as a KS2 teacher what you describe as expectations for Y6 I had for Y5 as I think they are easily doable for the vast majority of students, including those who find maths a challenge. That is one of the reasons I was and still am a fan of CIMT. It’s a personal failing perhaps but I have an issue with not teaching basic logic in Y6. I used to sneak it into my Y7 classes at the end of the year, when I was sure we had mastered the content as defined for the year.

On that we agree entirely!

It’s another reason I think it’s a shame we lost middle schools. I think it would be quite manageable to set a threshold of expectations for Y4 that any primary generalist could teach well, without worrying about the wider detail. That would leave specialists in middle and upper schools to take things on, rather than having to back-fill!

A really interesting post, not least because I am this very second coming to fairly similar conclusions while attempting to write an MA Education essay on the future of assessing KS2 writing without levels! (What else are half terms for?)

One thing that struck me about the NAHT’s desires is the contradiction inherent in their wish for ‘qualitative and concrete descriptions’. To my mind, the precision of criteria (which could account for greater reliability in that repeated assessments are likely to result in similar verdicts) often disregards the broader educational construct – what it is that we all agree makes writing good, beyond that which can be easily described – and thus is less valid. I feel that it is really important to preserve sight of the overarching construct and not get bogged down in the minutiae of atomised criteria. Clearly, that makes it very difficult for teachers to agree on summative judgements, but the minute we become reliant upon whatever could be the new equivalent to level statements, we risk placing too much trust in the imposed sequence and semantics of their phrasing. That’s why I’m inclined to disagree that a ‘traffic lighting’ system is intrinsically a bad idea.

My conclusion, however, like yours, is that exemplification is the way forward as it can allow us to marry both the concrete and the more holistic, qualitative descriptions presented as success criteria through illustrating them in practice. (At least, I hope that argument works out; my final essay’s due in very soon!)

Thanks for your comments BeeGnu.

Firstly, may I say that I’d be fascinated to read your MA essay!

Secondly, rather like my reply to Thom above, I wonder if we need to recognise a difference in how we tackle assessment across the age ranges.

My view is that agreeing “what makes writing good” is frankly rather academic at primary level. and perhaps part of the problem of assessment so far. We rush into “high level” features before ensuring that children are properly secure in the basics. I have marked writing in Year 7 of children who have achieved Level 5 in KS2, use a whole host of taught features that might be considered truly authorial, but who still struggle to punctuate sentences accurately. That cannot be right, surely? And yet any upper primary teacher deals with this all the time.

That’s why I suggest – at the primary level at least – a clear and concrete lists of expectations. How they are organised I’m uncertain about, and what exactly they are is not for me to decide alone. However, I feel quite certain that our first focus should be on ensuring that ALL children are able to secure these features. The current nonsense of Y4 objectives about including humour in writing, when many of those children are struggling to write coherent paragraphs is unhelpful.

I possibly have an unusual perspective in that I lead English (and assessment) at a middle school where we choose to teach KS2 in a tutor-based, ‘primary-style’, setting with KS3 following a ‘secondary’ model. We tend to find that great practice at KS2, particularly that concerned with a more rigorous approach to the teaching of grammar, for example (can anyone guess why that might be?!), is not just steadily raising pupil attainment in years 7 and 8 but is also benefitting KS3 teachers’ subject knowledge and subsequent practice. In that respect, I completely agree that the teaching of basic skills should be prioritised.

It seems to me, however, that a writer’s ability to work with ‘high level’ features isn’t reliant upon their age (though perhaps their maturity and experience, if such a distinction can be made), and so if a student is able to grasp an understanding of the passive voice, for example, (currently a feature specified in level 6 grammar tests) then we owe it to them to teach it. I currently teach in Year 6 (though have also taught at KS3), and frequently find I have a number of pupils who can employ semi-colons in a variety of complex sentences, due to a genuine understanding of both their grammatical purpose and nuance in text, yet fail to recall even the existence of full stops! That frustration, though, would in no way prevent me from introducing them to more complex punctuation. My personal feeling is that we should aim to teach just beyond our pupils’ current abilities (that’ll be Vygotsky’s ZPD then), and that includes alluding to less easily defined concepts such as the tone of a piece of writing. If primary teachers were to focus solely on the building blocks, then I fear children would grow up having missed the point (and the pleasure) – that writing is for the purpose of communication; clarity is essential, but so is an ability to entertain and manipulate a reader.

A further concern would be that if we were to use different assessment models for different ages, we’d risk losing that shared understanding of learning development, and what precious consistency there is on transition. I’m not sure it’s the criteria by which pupils are judged which are themselves the problem, but rather the superimposition of norms, now expectations, i.e. eleven year-olds ‘pass’ (yuk) at a 4b. At my school, our KS2 teachers have the luxury of seeing how pupils develop beyond Year 6 as a result of ‘secondary’ teaching and priorities, while the KS3 teachers can confidently gauge where their students have come from. Both groups are then able to adjust (and ideally continually improve) their practice in light of what they discover. There’s a lot to be said for encouraging the free flow of expertise between the phases, and I think that does rely heavily on the common language of assessment criteria and their interpretation.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

[…] Are Plans For Post-Levels Assessment Developing, Meeting or Exceeding Expectations? Michael Tidd A well thought out opinion blog on the NAHT report on levels (plus numerous other NC blogs that deserve a read). Michael’s blog gets to the heart of the challenges schools are facing, and he provides a sensible and coherent discussion of the issues. […]

[…] The NAHT released its report into the new landscape for assessment in schools. Having known for some time that levels were to be […]