I think one of the most useful qualities a headteacher can have is the ability to leave concerns behind at work. It’s never perfect – as I’m sure my family would attest – but if as a class teacher you find it hard to stop thinking about work in the evenings and weekends, then headship will only add to that challenge.

This weekend’s publication of a plan for music education feels like it was deliberately sent to test that ability.

True, you could say: never look at the news at weekends and never check your emails, but it’s not realistic. And so, early on Saturday morning I was presented with yet another document from the DfE telling me I’m failing. For that is how it feels.

Schools are different, so whatever you do, there will always be some school doing something better. Indeed because of the sheer volume of schools, you can usually guarantee that literally anything you do in a school will be done better somewhere. But as a head, so long as you can look at your own school and feel confident that you’re doing everything you can to offer the best deal on your priorities, you can live with that knowledge.

It becomes much harder when the government handpicks a small selection of examples and then tells every school in the land that what was the exemplar is now the expectation. It becomes an impossible task.

A couple of the case study examples in the new music plan talk about £20,000 annual budgets for music education in their schools. I just don’t have that money available. When I looked, half of the schools mentioned receive over £1000 more per pupil than my school: if someone put an extra £300,000 into my school next year, rest assured I’d find £20,000 for music!

Some of the (mostly urban) schools appear to be full, or even over subscribed. If each of my classes of 26 or 27 suddenly became 30, I might have another £60,000 in my budget which could certainly help music provision. But short of attempting to poach children from neighbouring villages or encourage more baby-making locally, there aren’t many options on that front.

None of which is to criticise what those schools achieve. The sharing of their practice is to be welcomed. We can always learn from other schools’ approaches, and can always strive to match those offers. But it’s not a level playing field.

So for government documents to state things like

The case studies included with this plan illustrate how excellent music education is being delivered now across the country within existing school budgets

is at best, unhelpful, and in truth disingenuous. Yet the DfE has chosen to all but insist that schools now create plans to bring their music curriculum up to the standard on offer in those schools.

Or, in fact beyond it. Even in their exemplar schools, not every one of the DfE’s bullet point list is met. Now you might argue that it’s important to be aspirational, but at what point are we setting people up to fail?

Music isn’t the only priority in schools. In the current climate, the massively underfunded need for recovery from the pandemic often tops the list; the near collapse of mental health services places a huge cost on schools both in terms of time and funding; demands for 90% attainment in English and maths will absorb both time and money. And neither of these things are in plentiful supply.

There isn’t a primary head in the land who wouldn’t like to give every child the opportunity to become proficient at piano. But for many, their first priority is ensuring that every child is fed, in a safe home, attending school in the first place, and hopefully mastering the basics that will set them up for their next steps.

None of that will be improved by a music development plan. Yet now school leaders will be forced to take time and money for other priorities to focus on this.

It’s demands like this that make me wonder how long the job is sustainable. Not because I don’t want to improve music education, but because I’m tired of constantly failing.

I’ve failed to get every child to attend school regularly.

I’ve failed to get 90% of my school working at the expected standard in maths.

I’ve failed to provide enough curriculum time for whatever subject Ofsted has lately pronounced upon.

And now I’ve failed to ensure that my school has enough practice rooms for music.

Never mind the fact that it doesn’t have enough space to provide calming spaces for all those children who need them because a special school place can’t be found for them. Never mind the fact that we don’t have enough teaching spaces to deliver decent interventions for those who desperately need to catch up. Never mind the fact that half of school leaders’ time is taken up with plugging the gaps left by failing local authority children’s services.

Now I must write a plan for how I’m going to create new practice rooms. Oh, and remove some teaching time from another subject to make room for more music lessons. Quite which subject they think we’re teaching too much of, I don’t know!

For me, this is the stuff that makes the job intolerable. I don’t mind there being SATs or an inspectorate. I can live with having to balance a challenging budget so long as it’s enough to pay for the basics. I can even cope with being on call on Christmas Eve to fill the gaps in the government’s pandemic strategy. But I’m tired of constantly being told to do more.

It’s exhausting to be told time and again that because one school has managed some accomplishment in some tiny part of their overall role, that we must now all do the same and more “within existing school budgets”.

When my time comes to jack it all in and walk, it won’t be the behaviour, or the parents, or the SATs that push me over the edge: it’ll be another damned expectation.

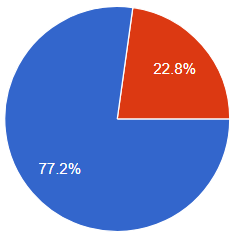

The greatest breadth in curriculum, at least in timetable terms, appears to be in Year 3.

The greatest breadth in curriculum, at least in timetable terms, appears to be in Year 3.